15 July 2020

You Are a Games Designer: Part II

If you haven't completed part 1 of this workshop, please click here.

So you made a game (or more) by hacking rock-paper-scissors.

What now?

Well, let’s take a closer look at what you created. What does your game say about you? Maybe you swapped rock, paper and scissors with objects that are familiar to you, or you injected memories from a trip, ideas from another game you played, a story you read or watched, or a conversation you had.

What you created is an expression of you. You have infused an old game with your own interests, and turned it into a new game that is meaningful to you.

Make your ideas playable

Have you ever thought about how you can tell your own story and express your own ideas through a game? We’re still not quite used to that kind of game. We are taught that games are “just fun”, they don’t mean anything. What’s the meaning of rock-paper-scissors? What’s the meaning of chess?

But if we look under the “fun” of any game, we’ll discover people, who infused those games with their own interests and their own idea of “fun”, just like you did with your own hack of rock-paper-scissors.

Sometimes we don’t know who invented a game, or we only know it was many people at some point in time to shape it the way it is. Still, those people had their own ideas, their own stories, their own meanings to express.

🤑 Do you know who invented Monopoly?

A visionary woman called Elizabeth Magie, who wanted to teach people about the dangers of monopolies (when a resource, such as land, becomes the property of very few people). She could have written a story, or drawn a graphic novel about monopolies. Instead, she thought she could make a game about them. She designed The Landlord’s Game with two different sets of rules:

1. Under the Prosperity rules, every player gains each time someone acquires a new property (designed to model a policy proposal of taxing the value of land), and everyone wins when the player who started out with the least money doubles it.

2. Under the Monopolist rules, players get ahead by buying up properties and collecting rent from all those who are unlucky to land there, and whoever manages to bankrupt the rest is the winner. Sounds familiar?

The Monopolist rules represent the reality of the property market, and Prosperity a vision for a better future.

Thirty years after Magie designed The Landlord’s Game, the Parker Brothers company bought the patent for ~$500, ditched the Prosperity rules and re-launched the game as Monopoly.

🤯 More than just fun

So you see, games can be more than “just fun”, and that’s what we’re going to learn next. How to make games that express your own ideas and tell your own stories. And if you want to make just a fun game (in your own sense of fun), that’s cool too :) But I want you to understand that you don’t have to limit yourself to “just fun”. Give yourself permission to explore all your emotions and make them playable, which is a beautiful way to share them with other people!

Start by picking a boardgame

In this second lesson we’ll continue using our hacking method you practiced with rock-paper-scissors, and we’ll split the process in two:

- Unpick a game, the focus of this lesson.

- Hack together and playtest your new game (next lesson).

🐘 What games are we going to unpick?

Hang on, when I say game, what do you think of? Probably a videogame. But you may have noticed that so far I have only mentioned boardgames. So here’s the thing. What you’re learning in this mini-course can be applied to all kinds of games. But I’m not going to teach you how to code, or how to use a game-making app. I’m going to teach you how to think like a game designer and how to make your ideas playable. For that, we’re going to use boardgames.

Because boardgames are quicker and easier to hack. You already know how to handle pen and paper, and that’s all you need to make a boardgame. You don’t need to know how to code. No need to worry about digital bugs. With boardgames, you are the game engine. You constantly process rules and check that other players are not cheating. This means that making a new board game can be as simple as agreeing to new rules between players! Like The Landlord’s Game, which is really 2 games you can play on the same board.

👾 But I don’t want to make a boardgame

I’ve seen many people getting excited at the idea of making a videogame, and then getting bogged down with software issues, getting frustrated at the computer not doing what they wanted, and giving up. So to spare you that pain, I’m encouraging you (and everyone) to start by hacking a boardgame. When you’ve made a few games and have become more familiar with game design, you can jump on making videogames (and I have some free tools to get you started with videogames in the bonus section).

🃏 OK what do I need?

So for this lesson, all you need is one boardgame to unpick. Don’t worry, you won’t be actually ripping the game components apart. When I say “unpicking” I mean playing it critically, asking yourself questions like “what is the idea behind this rule? what is the feeling behind this action? why can I do this but not that?”

There are some really intricate boardgames, which take hours to learn. We won’t hack those. There are also some boardgames that have very nuanced themes. We won’t hack those either. What we’re looking for are games that are simple enough that you can learn how to play them in 5 minutes, and abstract enough that you can quickly hack them with your own ideas.

If you already have such a game at home, you can go ahead and unpick that!

In any case, you can download and print one from this list. These are traditional games from around the world that exist in the public domain. We don’t know who invented them, or we only know it was many people at some point in time to shape them. Still, those people had their own ideas, their own stories, their own meanings to express.

🖨 From each game in this list, you can print out the board, then use pieces from other games or small objects you have at home, such as beads, dried beans, or even small bits of paper.

🤝 If the game rules don’t make sense to you, try searching online for a video, or other pages that explain how to play it.

🔀 You may find several ways to play the same game (people in the past have already hacked that game :) so don’t be too precious about figuring out every single rule. Start playing it, and fill in the rules you can’t find with your own common sense.

✋ Do you have a board game in mind for this list? Suggest it using this short form!

🎯 What's the point?

By unpicking an existing game, asking many questions about how the game works and why, you’ll start seeing how you could hack it into your own game.

🧱 When I was a kid I loved playing with Lego. And even now, when I make a game I still think of it as something made out of Legos. Each rule, each piece, is a Lego block. A rule is an imaginary block, but still, something that you can unpick from the rest of the game. What you’re about to do is separating all those (game) blocks, so that you can start reassembling them in many different ways, leaving some blocks out and adding new in, and in that way you build your own game (which, by the way, is much easier than starting a new game from scratch).

Let’s unpick that game!

Once you have a game to hack, how exactly are you going to unpick it?

Let’s see. What sets games apart from other media, such as films or comics (pardon, graphic novels)?

Can you play a book? (Not quite) Can you sit down and just watch a videogame? (Yes, as long as someone else is playing it..) You may start to see what makes games different. In games, people need to be active!

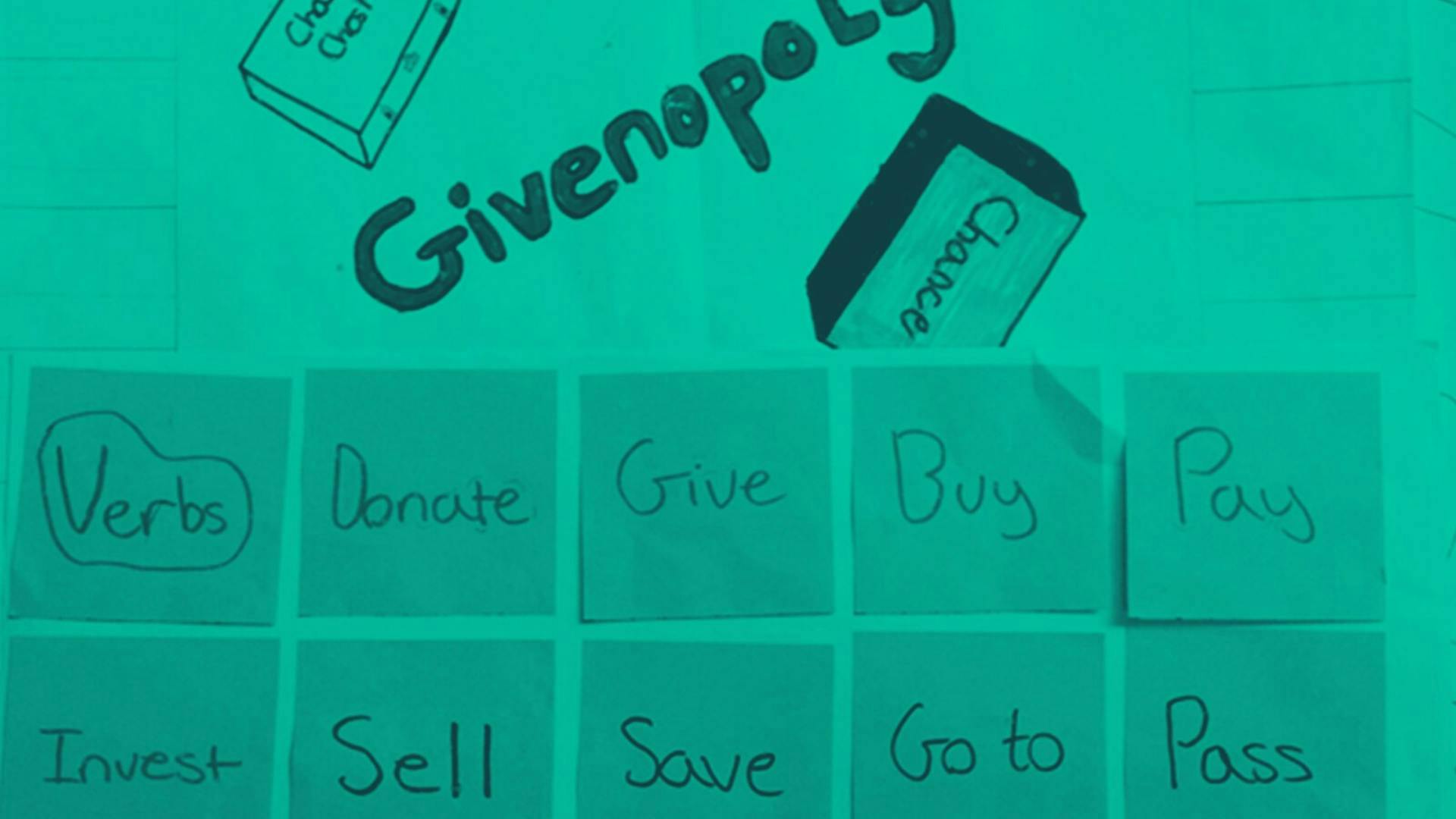

Whether it is running or collecting, shooting or trading, games are driven by actions, aka verbs: verbs define what you can do in a game, how you can interact with its characters or other players, what you should do to win it, and what you simply can't do.

Think of a game you’ve played recently. What actions does the game allow you to do? And what does the game not let you do? For example, what if you tried to talk to an enemy in a shooting game (like Fortnite, is it still a thing?) instead of shooting them? Why not?

🧐Get ready to play your game critically

We’re going to unpick the verbs of the game you decided to work with.

Click this link to access a handy worksheet (you can either print it out, or make a copy and fill it in on your computer).

As you play your chosen game, keep the worksheet handy so that you can jot down your notes on its verbs, as well as ideas on how you may want to hack it!

Give yourself no more than an hour to do this, ideally more like 30 minutes. You don’t need to have played a whole game or understood all the rules.

🔜 What next?

After you’ve come up with a few hack ideas you’ll be able to pick the most interesting one and start turning it into a game draft, aka a prototype. Good luck!

Unpicking verbs is one method that works well for people who are not yet familiar with designing games. If you want to dive deeper into this, let me tell you that game designers and researchers have put a lot of thinking into defining what games are, how to analyse them and how to make them. My suggestion for a next step for you is the MDA framework to analyse game mechanics, dynamics and aesthetics.

Go to PART 3: Making Games Fast >

Stay up to date

It's time to level up your inbox

Pick which newsletters you're interested in receiving, and customise further by specifying a discipline.

Join our mailing listTell me more